3D body scans were once thought to be an elixir for the customer fitting process in retail stores but the reality is that these tools can’t do everything that a human can. This concept of 3D simulation had been tossed up by the technologists a few years ago, and the fashion industry, initially, seemed quite optimistic for the kind of potential these tools have. However, after years of innovations and technical development, the industry now is not speaking in the same voice and is divided on two fronts: one talks about what it can do and the other is not so sure about its feasibility in complex products such as bra, swimwear, and to some extent, activewear. The restriction is not just limited to scanning the complex areas of a human body but it is not even a definite thing to say the fitting can be perfect for various body postures. There is no doubt about the capabilities of 3D simulation as they are great at acquiring data, but they are not quite ready to make tough decisions yet. Beyond the body-scanning machine, a critical part that makes the process work is the software that interprets the data from the scan — the technology that still has a long way to go before it replaces a human’s assessment. I interacted with 3D fashion industry pioneers to figure out the areas of limitations of these tools as well as how to overcome these restrictions.

Body scanning is a non-contact, 3D measurement system that uses infrared depth sensing and imaging technology to produce a digital copy of the surface geometry of the human body. This scanning generates a silhouette of the shape and an extensive list of body measurements. The 3D data then can be exported for pattern construction, garment draping simulation and 3D body tracking.

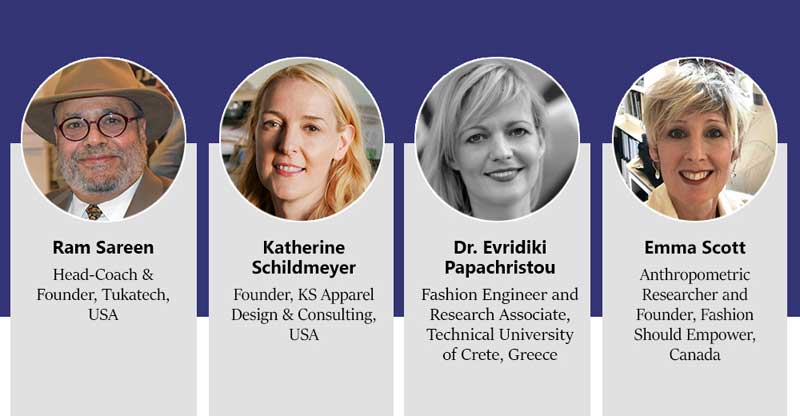

According to Ram Sareen, Head-Coach & Founder, Tukatech, USA, “Nearly any apparel product can be simulated in 3D, but the most value by adding 3D to product development comes to companies which are driven by print/graphic design.” Once a pattern is simulated as a 3D sample, it becomes an asset that designers can utilise for future reference or repeat silhouettes. “In our TUKA3D Designer Edition, designers continue to work in graphic design software programs they are already well-versed in, but now they have a 3D croqui to visualise artwork instead of a flat sketch,” commented Ram.

However, Ram opined that there are certain challenges that exist in 3D simulation that cannot be overlooked. One of these challenges is with fitting bras in 3D as part of the assessment involves evaluating the morphing of the breast to the cup, wires and whatever fabrications. A typical 3D cloth simulation engine calculates fabric physics against a rigid 3D body. For bras, the physics of the cloth and the breast would both have to be simulated against each other, which would generate a very complex 3D mesh. The computational requirements are much greater and much more time-consuming than what fashion businesses can afford to spend in sample fitting.

Dr. Evridiki Papachristou, Fashion Engineer, Research Associate, 3D Expert, Technical University of Crete, Greece too supported whatever has been said above. According to her, missing data from hidden areas of a 3D body scan, change in the posture of the body during movement, surface texture and body landmarks are some of the challenges of 3D body-scanning technology. However, in a recent International Conference on Computational Modeling & Simulation, researchers presented the dynamic simulation of 3D virtual wetsuit. Diving activities frequently happen in the cold sea, river, lake and other places, as a result, the construction of the wetsuits plays an important role in thermal protection and restricting water circulation around the body. 3D simulation of wetsuit on virtual human body at first seems not feasible since it involves different postures and movements of the diver which could result in a too loose wetsuit or a too tight one.

“However, through the use of 2D and 3D technology and 3D parameters’ adjustments, some real properties such as the contact performance can be simulated on the 3D avatar. Exact mimic and measurement of garments like bras and swimwear is difficult because in the case of swimwear, movement especially in water affects the body measurements. The interactions between body shapes, pattern shapes and fabric properties which can be found in bras, can create an exponential number of possible fitting issues to be resolved.”

Endorsing the same, Katherine Schildmeyer, Founder, KS Apparel Design & Consulting, USA, asserted that a big problem of body scanners is that the scanners feed body measurements into one another when there is skin folding over itself. “For example, a breast hangs over the underbust line. So, the scan feeds the drop of breast into the underbust and can’t calculate the full arc of the breast for a bra,” quoted Katherine.

Not just bra, the same problem arises when scanning of plus-size apparels is tried using 3D simulation. “In plus-size, the biggest issues are tummy hang and thigh in

relation to crotch point and torque,” stated Katherine. For a moment, one can scan a smaller body with much less body fat to it. Using 3D design programs with small size avatar does allow for easy design of all aspects of clothing due to the lack of tissue folds. Body scanners can also easily scan body types like this and come very close to actual measurements due to clearly defined measurement points.

To give broader view as to what kind of limitations exist in measuring data using 3D in plus-size body, Katherine further highlighted some of the bottlenecks mentioned below:

1. Stomach – If the stomach has tissue overlap, it will measure the stomach at a larger range.

2. Across Underbust: In this case, the breast hangs over the underbust line. This will cause the breast mass to scan in as the underbust rather than the breast. This causes poor measure balance across five points of measure.

3. Rise measure: If the lower gut hangs over the pelvic floor, it will also result in an inaccurate body scan.

4. Centre-front Chest Gap: In order to create a bra strength, this zone is also a measuring factor. Body scanners can’t accurately gauge the zone due to tissue overlap.

5. Crotch Point and inner thigh: This zone has chaffing and also a rotational shape the scanners can’t pick up due to overlap of tissue. The inseam will also change as a result of the body mass in relation to the rise.

“It’s recommended that we work with it as an aid or a helping tool rather than entirely relying upon it,” opined Katherine.

3D or pattern–making practices… What is to be blamed?

Emma Scott, Canada-based Fit Specialist, Anthropometric Researcher and Founder, Fashion Should Empower agreed that 3D technologies have not yet presented the apparel industry with positive outcomes; it is her opinion that these results reflect foundation flaws in pattern-making practices and not limitations within 3D. Using the gauge of limited impact, it is easy to surmise failed technologies, yet globally, other manufacturing industries have been radicalised by 3D technologies.

Why then has the impact within apparel been nominal and the digitisation of apparel stalled? Emma pointed out that 3D scanning for measurement extraction has been fine tuned to accommodate countless proprietary land marking and measuring methods, and proven accurate to the mm, yet many continue to claim scanners offer inaccurate measurement data resulting in poor fit. “With companies using different measuring protocols, a lack of cross platform data compatibility has created immense digital redundancy,” explained Emma, further elaborating, “Libraries of Avatar Databank are available to assess body shape, yet patterns designed for these shapes still require garment fittings (whether virtual or physical) to perfect ‘fit’ on human body.”

The common thread found in any review of the impact of 3D technologies on the apparel industry (a lack of direct relationship between the body and garment pattern) suggests the limited impact of 3D technologies within apparel which is related more to methodology than to technology. “Quite simply, our pattern engineering methods are founded on practices that do not account for global variation in body size. This has been proven time and again by universities all over the world; any method of pattern-making will successfully accommodate the body shapes of a select group of individuals but not others. The roadblock to apparel digitisation is a lack of pattern engineering methodology with direct relationship to the body such that posture and gender can be ascertained from measurement alone,” asserted Emma.

Few examples from global apparel industry where 3D scanning did not work

What experts have opined above can be heard by most of the industry pioneers who tried 3D for bra/plus-size/swimwear but failed in some way or other. One must do fit sessions to really ensure that the avatar that was created is a full match to the actual person and this is quite difficult to achieve. “I develop avatars but it still can be a miss on rise arcs and breast slope and fullness,” accepted Katherine. Beyond the hundreds of thousands of data points collected by the scanners, a critical part of the fitting process is learning about the person, including their lifestyle, habits and posture patterns — information that can only be collected by observing them and interviewing them. In the scanners, the person is in a static pose which is actually forced on him/her. Restrictions start from here as it is difficult to analyse the postures of the person once he/she wears the product.

1. Japan-based fashion retailer Zozo reported a drop in profits following its failed experiment with a body-measuring suit in November 2018, which was its main business model. So, recently the retailer had to shut down operations in USA and Europe.

2. Acustom Apparel, where customers can buy custom-designed suits with the help of a body scanner, has realised after years of practice that 3D body scanning can’t capture the entirety of the fitting experience — the subjective feel of the right fit, variations in posture and other customer preferences.

3. Indochino, a specialised custom fit menswear, doesn’t use body scanners as it can’t replace human element from it. Instead, it uses a try-on program in its showroom where customers try on standard template sizes in three silhouettes to determine the closest fit; staff members apply a series of fit tools through a proprietary app to address any fit issues prior to construction.

4. KS Apparel Design & Consulting had a client try a 3D designed bra by a company called Evelyn & Bobby. It took four rounds to get the right fit. It still didn’t work well. Katherine concluded what the fit issues were and noted that the 3D approach to inclusive design for breasts was the key problem; mostly because the foundation of the programs doeshave limitations. The company has now changed the focus, sighting that not every bra is the right fit. “Many of such companies that solely rely on 3D body scanning for extended sizes are failing big time,” claimed Katherine.

5. Evridikitold that in late March of this year, NASA cancelled all-female spacewalk, citing lack of spacesuit in right size. Fit visualisation interfaces are based around an avatar and tension maps where the wearer or producer can assess how tight or loose a garment may be. The final decision of the spacesuit’s appropriate size was made after a spacewalk, but it was too late to reconfigure a new one.

However, Ram Sareen had a quite insightful observation to share on the use of 3D by retailers. “We were implementing TUKA3D for a vendor working with a plus-size brand. They kept getting feedback from the brand that the 3D rendering was draping so differently on the live fit model that it almost looked like a different style, and it was impossible to approve virtually,” said Ram.

Being a pioneer in 3D simulation, Tukatech did some digging and found that the brand rotated between two different fit models but had only shared data to replicate one of the models as a 3D avatar. This meant that half the time, the brand was comparing the TUKA3D rendering to a live model with a completely different body shape and posture than what was shown virtually. After this realisation, the brand understood that they could only compare the 3D rendering to the physical sample draped on the corresponding live fit model. This exercise also showed that the two fit models they were using were so different in proportion that the brand could never expect to see a consistent drape between the two women, let alone between the women and a 3D model.

Future of 3D technology…

3D body scan of a large number of people without any physical contact has facilitated national size surveys, which generated anthropometric data for research and other purposes. However, these busy measurements must be updated and accurate especially for complex products that involve movement, sports, or uniforms. Allowed tolerance for a jacket is completely different from a pilot’s helmet, a spacesuit or other functional clothing. Evridiki opined, “The measurements from 3D body scanning are very reliable, but protocols for locating body landmarks still need to be perfected. Fitting the complex shape of a human body is a difficult task, even with body scanners and 3D technology. Certainly, one size does not fit all but 3D technology in the last two decades has overcome many obstacles and new systems are more mature and it is even more possible to provide well-designed custom-fitted clothing products.”

Emma shared that the numerous CAD available ensure that there are digitised environments to suit the unique work styles of a global population. Once the foundation flaws in pattern-making upon which these environments are built are corrected, the promises of 3D technologies will be realised. “As with the growth of all technologies, the initial years of apparel digitisation have been painfully slow but the tipping point has arrived. It is my prediction that the exponential growth we have witnessed in the digitisation of other industries is about to hit apparel,” said Emma optimistically.

Talking about the futuristic approach for 3D, Ram Sareen explained that the future is less about the tricks and tools and more about how a 3D workflow sits within a larger product development process. “We have always believed that a TUKA3D sample should completely replace even physical fit samples. Companies which are using 3D only for visualisation are still wasting time in product development. After the 3D sample is approved, they still must see two or three physical fit samples before they can go to production because the visual did not match reality.”

How Tukatech is fiercely innovating to combat fitting challenges…

In order to maximise the TUKA3D sample-makers’ time, Tukatech launched the TUKA3D SMARTqueue, which uses a company’s TUKA3D computer network to keep processing renders and simulation even after a 3D sample maker has gone home. This is valuable for complex products because it lets the 3D sample makers focus on the creative input, while the processing happens in the background.

For every TUKA3D implementation, the first step is to replicate the live fit models as 3D virtual fit models. This includes taking measurements, as well as capturing the shape and posture of the live fit models. Besides TUKA3D models are always rigged with real-time motion simulation, so that virtual fit sessions happen in the same context as live fit sessions. This practice is useful for fashion garments, as customers expect a level of functional comfort in the clothes they wear, but any brand or vendor using 3D to fit athletic garments should view motion simulation capabilities as a requirement in their virtual product development process. “Without motion simulation, you will never be able to evaluate the garment beyond the look,” quoted Ram.