cost by 30-60%

The production of Chino pants and shirts in Bangladesh is higher than in other countries. Both products offer a vast opportunity to minimize the manual work in an industrial production. The regularity of both products is conducive to the use of special aids. Whether one draws guidelines on the machine table or uses a swing-in folder on the machine occasionally, it can be decided after a constructive analysis of the operations. The fact is that the above-mentioned products, even if they are fashionable, offer large potential for rationalization. This first article of the two-part series, discusses the organization and control systems required for a smooth running of production.

The production costs can be minimized and the competitive position in the market improved. But it is very important and must always be kept in mind that rationalization must never be at the cost of quality. The steps for rationalization are as under:

• Sort the garments into modular groups

• Construct a work flow pattern

• Document history setup before making any changes

• Make changes to improve savings

• Calculate tact time to create theoretical material flow

• Divide long operation into smaller elements

• Re-engineer workplaces wherever possible

• Develop floor layout plan.

Before making any machine plans or changes, we must gather information on all styles to be produced, and analyze the sequence of operations necessary for each one of them. While doing this, we try to sort the individual garments into modular groups such as fronts, backs, legs, assembly and finishing. Within these modules we find that the operations are quite similar, whereas in the small parts, sleeves, pockets, collars pre-assembly, etc. the work content can vary vastly. From these analyses we can construct a rough picture of how the workflow will have to be, by going through certain procedures and set targets.

Step I: Set Targets

1. Target costs (target improvement and return on investment)

2. Human targets (improving working conditions)

3. Organization targets (improving material flow)

4. Deadlines (project progress and deadlines for the rationalization and improvement of delivery dates, throughput time reduction)

5. Delegate responsibilities.

Once the targets on cost, working conditions and material flow have been defined we can start with the project implementation. The first step is to document the present situation before any changes are made. These figures can later be used to justify the changes that are undertaken. These figures should also prove that wage earnings and performance after the changes are at least at the same level as before the commencement of the project or showing increase in savings, but not at the expense of the workers. Last but not the least, the product quality must not suffer and increase in productivity must never be achieved at the cost of quality. A useful benchmark for production is the pieces per head and this is calculated taking into consideration all workers in the line, including helpers! This is possibly the most important outcome for comparison after the changes have been made.

It is now time to take the next step, the purpose of which is to define the actions to be taken by the project team.

Step II: Set Tasks and Scope of Project

1. Scope of system (number of people involved and affected, machines, product groups, etc.)

2. Rationalization through weak point analysis

3. Project team (the four “Ws” – Why, Who, When and What – should be defined and followed throughout the project)

4. Deadline planning (tasks and targets that are possible with the selected project team).

It is useful to make a material flow diagram in which the changes in organization are visible. It is very important to convince all involved in the project of the advantages of the changes and get their valuable input. This is one of the guarantees for a successful project. Apart from the style range, there may be operations that are needed in other production sections that are geographically close. (This aspect is discussed later on in the article). Before proceeding to the next phase of the project planning, initiate a brainstorming session. This will then be the third step in the process.

Step III: Solutions

1. Discuss and document possible solutions

2. Implement problem solutions.

There are two different ways of planning equipments on the shop floor. The first is the grouping of identical or similar operations and the other provides us the styles that require a similar material flow. The issue to discuss is which of these alternatives will bring the least chaos in the production cycle. The most important factor for the production is that as little as possible should go backwards in the material flow. Those operations that require a backward flow can often be eliminated through changes in construction. When new styles are developed, the sewing department must be aware of the flow problems in the production.

Using a trousers production, for example, we can illustrate how production can be reorganized in an existing area. Assuming that half the area was used for the production of jackets and the other half for trousers, the first planning step is to take a bare layout plan of the building since every production area has its restrictions, and also there are rules regarding emergency exits and isle space or distances from the walls. Once these requirements have been understood, we can start planning the production floor for a certain product or range of products. The first task is to set the tact time (also called pitch time). This time is required to calculate the number of machines and workers required. It can be calculated as following:

Total SAM / No. of operators = Tact time

For example,

40 Minutes / 50 operators = 0.8 mins tact

The above example shows that a theoretical material flow is created in which an operation is finished every 0.8 minutes. This figure is the basis for all planning calculations. If we have an operation of 1.2 minutes, we know that it will require 1½ standard operators for the job, or we will produce 600 pieces in an 8-hour period at 100% productivity.

When making the operation bulletins we have to decide about the work division. This means that we can decide to have one operator make a complete part, e.g. welt pocket, or divide the elements between multiple operators. Investigations have shown that the optimal length of an operation lies between half and one minute. Shorter operations become very monotonous and longer operations require increasingly more time to adjust to the rhythm of work. A further criterion is the size of the production lines.

Let us take the example of sewing two welt back pockets in a pair of trousers. The operation using a normal straight seamer with under-bed-trimmer would be 6.8 minutes. In the first place the operation takes a longer time to learn as the repeat effect comes at very long intervals; secondly, the number of operators required in a line with 0.8 minute tact will be more than 8. Even in a small sequence or production runs, it is necessary to divide such operations into smaller elements as the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. For instance, in case of long operations if any problem occurs, be it an operator mistake or bad cutting, the interruption in the work process will take a longer time to overcome as the operation cannot be learned by other utility operations quickly. The disruption can take days to correct and the excess costs are very difficult to calculate. These costs must not be underestimated.

When we talk of an economical production, we would say that a trousers production is most efficient when the daily quantity per shift lies between 1,200 and 1,600 pieces. This figure is governed by a number of factors, including human performance; the machine part also plays a major role. Every industrial product has its own most economic batch size per shift. Before deciding how technical a machine is to invest in, the operation should be split up into part operations. In the case of label attaching, one should consider whether this can be done in advance as a separate operation. Further, attaching the pocket bearer in advance is possible, as well as closing the bag after setting the welt. Many production units use this or similar split down of operations (see Table 1 in this case, including button hole sewing).

Before making any changes in the material flow, one should use the chance to re-divide the operations which are too long or combine those which are too short. One must also keep in mind the possible costs of additional machines, suitable operators, etc. Further, there is also the possibility to use a stop-watch to measure the motions, which are part of a sewing operation to be reshuffled. When increasing the number of operations, there will be an increase in the throughput times as more people will have to take the pieces in their hands. These additional times cannot be measured with a stop-watch, since the increase in productivity comes from advanced training on shorter operations. The operations can be further refined by engineering the workplaces to cope with the new operations. These changes provide a new situation that makes a change in the workflow possible bringing in cost savings (Figure 1). Now in a brainstorming session, the team can think out a variety of possible workplaces and flows as well as systems and operation sequences.

On the basis of a standard operation bulletin for a specific product/style to be produced, we can allocate required quantities which will be used for the development of a material flow without or with minimal backtracking. We have taken a trousers production to demonstrate this procedure, but whatever the style, once identified, must be accepted by the entire project team. This is very important at this stage, as once the electric connections and relaying of steam pipes is done, there can be no more major layout planning changes.

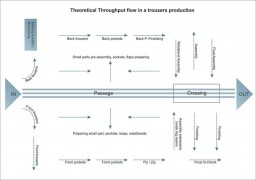

The flow in Figure 2 is from a project that involved reorganizing a jacket and a trousers factory into a pure trousers production by having a separate cutting room. The production room was sufficiently large and the trousers had previously been produced in the northern part (top half) of the room. The reorganization allowed the company to make changes to improve every operation. The investment and improvements allowed the company to reduce the production times (Standard minutes) by 25% for a pair of trousers. Once the new plan and layout have been accepted, it is time for the fine planning.

The next Step for the project team is to allocate the individual machines for each operation. This is where the quantity of machines and operators are determined. Now we can make the first draft layouts on a room plan using templates to represent the position of each machine in the operation sequence. By doing this one can see where backtracking occurs and take corrective steps. The main task is to reduce throughput times and distances which will give us a better estimation of the delivery dates to be expected.

A smooth production flow can be documented through a daily excess costs analysis (see Table 2). The excess costs are a measure of the efficiency of management and supervision. The excess cost control shows the difference between the theoretical calculated wages and the amount actually paid. These figures are a by-product of any incentive system where the individual performances are monitored. The local laws may influence the degree of information that can be collected by the daily performance controls. Excess costs are always of great importance in a cost analysis and gives us a chance to get them under control, when we know how and where they are being generated.

In cases where one deals with multi styles and short runs, the classic line system is doomed to fail. This would be caused by:

• Constant relocating of machines

• Moving operators from machine to machine

• Waiting times due to upsets in the material flow.

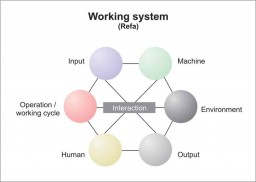

In order to avoid these costs and still follow a rationalization strategy, we must take a different approach to the machine layout. A flexible (modular) production system needs more machines, i.e. less machine utilization, with higher investment. The production costs will always be higher than in a conventional standard shirt or trouser production. Fashion production requires a much higher degree of management skills for the balancing and throughput of smaller batches. The supervisors must be well prepared for a change in this direction and involved from the start of the layout planning. The flexible layout uses skill centre modules, (see Figure 3) setup in an open architecture. This abstract scheme is designed to show the interactive working of the skill centres and not the physical layout.